Beyond sustainability: radical re-imagination and creative responses to the climate

Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world, stimulating progress, giving birth to evolution.

Albert Einstein

We are shaping the future we long for and have not yet experienced.

adrienne maree brown

In volatile and complex planetary times, the role of the arts is more important than ever, helping us to make sense of the context in which we exist. Artists and creative practitioners are interpreters, navigators, empaths and architects, seeing beyond the immediate to what lies ahead.

Historically, societal tumult has provoked inspirational artistic and cultural movements, from the Renaissance to Romanticism, Weimar to Afro-futurism, Beat culture to Punk. Much of this work, now recognised as era-defining, came from the margins, from artists responding to the socio-political contexts of their day. At the time, the cultural work of these eras was largely regarded as tangential, but in retrospect, the work has contributed to and continues to influence the future in extraordinary ways.

Fast-forward to the 21st century, a time when the environmental crisis is more urgent and indisputably graver than previously understood. The most recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) stated: “Rapid and far-reaching transitions across all sectors and systems are necessary… The choices and actions implemented in this decade will have impacts now and for thousands of years.”[1] The scale of the transition required is enormous but making changes is undeniably slow.

In response, in March 2023, Christiana Figueres, who from 2010 to 2016 was Executive Secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and an architect on the historical Paris Agreement, presented a compelling case for what she called “flipping the environmental narrative. Everything we do still counts,” she wrote. “The rest of the story of repair, regeneration, and connection still needs to be written, and the pen is in our hands.” [2]

A crisis of imagination?

Building on Figueres’s provocation, it’s striking that despite mounting scientific evidence of the scale of the environmental crisis, stories of repair, regeneration and connection are not widely prevalent in culture today. A key reason, posited by Professor Geoff Mulgan in his book, Prophets At A Tangent, is a crisis of imagination:

“We are suffering from a serious deficit of political and social imagination. The oddity of the early decades of the twenty-first century is that it is easy now to imagine technological futures and easier still to imagine ecological disaster, not far in the future. But most people struggle to imagine or describe how our society, our democracy, our welfare, or our healthcare could evolve for the better over a generation or two. Our capacity to imagine has been stunted. Instead, pessimism and fatalism have become the default.” [3]

Surely then, as Figueres has suggested, the need to flip the narrative is more important than ever? And arts and culture have a central role to play.

Thanks to the work of organisations such as Julie’s Bicycle and BAFTA’s albert, many cultural institutions and organisations are embracing environmental responsibility, and reducing their carbon footprint. The UK’s 2050 net zero target provides a clear societal goal, regardless of the current government’s prevarication.

But flipping the narrative about the inevitable societal transitions that are unfolding goes far beyond decarbonising outputs and mitigating emissions where culture is traditionally housed. Artists and creative practitioners are essential to surmounting society’s imagination deficit. But harnessing this potential is going to require the cultural sector to go beyond sustainability at the highest levels.

The role of culture in the environmental crisis

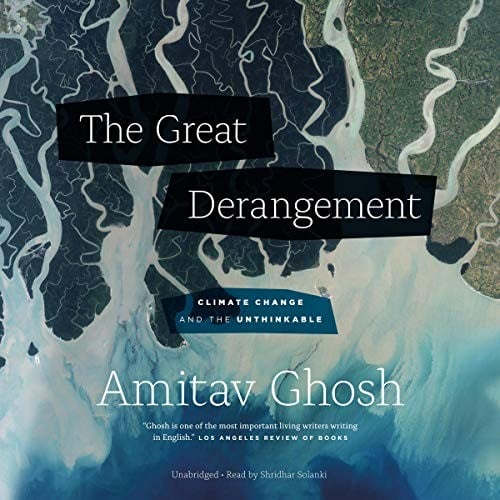

Writer Amitav Ghosh states in his book, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable (2016) that future generations will condemn a collective imaginative failure to grasp the scale and severity of climate change:

“When future generations look back upon the Great Derangement they will certainly blame the leaders and politicians of this time for their failure to address the climate crisis. But they may well hold artists and writers to be equally culpable – for the imagining of possibilities is not, after all, the job of politicians and bureaucrats.” [4]

Writer and cultural intellectual Rebecca Solnit similarly reminds us of the need for imagination in creating possibility, and goes further: “There are so many doom-soaked stories out there – about how civilisation, humanity, even life itself, are scheduled to die out. This apocalyptic thinking is due to another narrative failure: the inability to imagine a world different than the one we currently inhabit.” [5]

The good news is that there’s innovation happening across the margins of multiple sectors of society, from renewable energy to community activism, green transport to regenerative farming. Increasing numbers of pioneers are engaged – and in some cases highly successful – in finding inclusive solutions to the impacts that the changing climate and its implications bring. Through the clouds of media disinformation, signs of progress are beginning to seep through into the mainstream, some thanks to major financial investment, others as a result of people-power, catching businesses’ or the public’s imaginations and taking hold.

This is mirrored at the cultural margins, too, where individual creative practice about the environment is burgeoning. There is a diverse range of artists working in a range of forms addressing the complexities of this inherently intersectional crisis in new and interesting ways – Fehinti Balogun & Complicité’s brilliant filmed performance piece, Can I Live? launched online via the Barbican during the pandemic is just one example.

But like any other form of innovation, resonant work at the cultural margins requires support to accelerate and amplify it, propagating compelling, scalable new ideas. Otherwise the potency of visionary work risks languishing unrecognised at exactly the moment it is needed, until the retrospect of history corrects any oversight. And in the case of the environment, that’s too late.

Reimagining creative catalysis

Without doubt, the reimagining required to flip the environmental narrative in the current cultural funding landscape is challenging. Creative development initiatives can seem like a phenomenon of some pre-pandemic utopia.

Few schemes support the nurture of early-stage ideas. There is a high degree of attrition, and risk aversion often leads to supporting work that’s much more evolved. But this type of creative development needs investment, to allow it to be showcased in high profile ways. Investment in cultural leadership is also needed, for this is where gatekeepers reside.

The margins of UK civil society provide refreshing inspiration, where there is impressive momentum around the concepts of Imagination Infrastructure and Imagination Activism. In what could be considered a form of civil society-creative development, this growing ecology of people and organisations, supported by funding from organisations such as the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF), is investing in growing and maintaining the capacity of specific communities to collectively imagine. By co-creating visions of the future together, new narratives and pathways are cultivated towards a shared north star.

But despite what is inherently an intensely creative approach, interestingly, very few of the forward-thinking organisations and practitioners within these networks would identify as artists. One notable exception is the ground-breaking MAIA. Artist and writer Lucy Neal, visionary co-founder of the London International Festival of Theatre (LIFT) is another.

As Neal says in her recently re-published book Playing for Time: Making Art As If The World Mattered, “Practice is key to how art takes up the challenge of rethinking the future.” [6]. But what are the practices needed for the UK’s cultural sector to embrace its highest potential and rise to the challenge of reimagining what’s to come?

There are compelling learnings in the interdisciplinary model evolved by Cape Farewell, an artist-led organisation, which, since 2001, has been working to create urgent cultural responses to environmental change. In the past 15 years, it has supported more than 300 artists in the research and creation of artworks, bringing together creative and scientific minds to work with frontline communities affected by climate change, entrepreneurs, sociologists and universities to create new artistic interventions and works.

Enabling more creative R&D spaces, “containers of reimagination” – be that institutionally or otherwise – bringing together artists with a range of other actors in the climate crisis, would allow for new co-created work to unfold. Through illustration, Fine Acts, a creative studio, works in this way, bringing together visual artists and changemakers in collaboration through financially-incentivised creative briefs. The energising and diverse work that’s created is made publicly available for non-profit use through a creative commons licence but is available for commercial licensing in their curated free vault, The Greats (check it out!).

Cultural work emanating from socially engaged cultural practice in community provides important insights too. Take initiatives such as Invisible Dust’s Breathe: 2022, created by Imperial College scientist artist Dryden Goodwin and the community of Lewisham. Or the collaborative community-based enquiry into the role of arts, heritage and storytelling through the Community Climate Resilience Through Folk Pageantry project in Manchester.

What might creative practitioners contribute to our vision of the future, if they were better enabled? Their ideas and inspiration, radically unleashed, would be an antidote to either the “doom soaked stories” to which Rebecca Solnit refers or a vacuum of denial when it comes to acknowledging the societal transitions that are coming.

The imaginative pathways they would open would be exhilaratingly fresh. [7] Photo credit

Reimagining the propagation and scalability of new ideas

As I write this, I’m glad to acknowledge the vibrancy of the programming of the Southbank Centre’s Planet Summer this summer, a multi-dimensional season that showcases an extraordinary range of work and ideas. It inspires a call for action that all of us, making change together, can address the challenges of the environmental crisis.

To be clear, there are plenty of individual creative practitioners busy reimagining, but their work is obliged to compete for increasingly diminishing public funding against other more popular, audience-grabbing and mainstream ideas. Larger-scale programmes that support individual creative practice, with a few pioneering exceptions – such as Doc Society’s Climate Story Unit, General Ecology at the Serpentine and the Design Museum’s Future Observatory – do not yet exist.

The investment of philanthropic funding into a range of re-imagination initiatives within culture – with a specific focus on the environment – would allow for the generation of fresh thinking, and a multiplicity of ideas and content to emerge from explorations of overlapping issues and intersections. It would also provide valuable opportunities to enable new, inclusive practices, placing the expression of nature, climate justice and regeneration at its heart.

But it’s not just about funding. For cultural work to engage an inclusive range of audiences (which is critical), a constellation of other partners – policy makers, industry leaders, activists and communities – is essential to informing, accelerating and deepening the way in which the work resonates. Taking a systems-led approach, powerful interdisciplinary collaborations such as those of the racial justice-focused Pop Culture Collaborative in the USA, whose CEO Bridgit Antoinette Evans who talks about seeding “narrative oceans” and its UK version, Power of Pop Fund, are busting silos and placing authentic creativity at their heart. The UK’s academic sector also offers learning through the energetic interventions of University of the Arts London’s (UAL) Climate Emergency Network and King’s College London’s SUPERBLOOM, among others. Maybe there should be more creative R&D spaces created in universities for creative practitioners more advanced in their careers, offering pathways to a range of audiences in partnership with cultural institutions? The UAL Storytelling Fellowship (part of the AKO Storytelling Institute at UAL) which is currently focused on disinformation, is an interesting model in point.

In Conclusion

As John Berger says in his book Hold Everything Dear, “An interdisciplinary vision is necessary in order to connect the fields that are institutionally kept separate’”[8]. It’s one of the many unique properties that arts and culture can offer to the challenge of reimagining in these critical times. Not least because the climate crisis is one of complex intersections, and potent cultural responses to it require an equivalency of approach.

Clearly, it is also going to require investment of funding to allow for a multiplicity of ideas and creativity to emerge from the cultural margins, be that new models of artistic discovery, new platforms to build co-operation, or innovative artistic practice. Only then will new narratives of transformation – such as the stories of repair, regeneration, and connection that Christiana Figueres has called for – be enabled to germinate and grow.

The scale of the societal transitions that are coming and how they are interpreted, articulated and understood implicate the whole of the arts and cultural sector as re-imagination change-agents. As I heard Farzana Khan, arts-educator and founder of Healing Justice London say at an event the other day “The rigour of this time demands vision not imagination”.

So whether it’s re-imagination or vision, the time is now. Cultural work addressing these changing times demands to be era-defining. As cultural leaders and practitioners with the responsibility to enable it, we all need to go beyond sustainability and step up.

Jessica Edwards is Head of Cultural Development at Nesta, joining in July 2023 after her Clore Fellowship.

Notes to Editors

[1] IPCC AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023

[2] Christiana Figueres, Flipping The Environmental Narrative (Project Syndicate, 2023)

[3] Geoff Mulgan, Prophets at a Tangent: How Art Shapes Social Imagination (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023)

[4] Amitav Ghosh, The Great Derangement – Climate Change And The Unthinkable (Chicago University Press, 2016)

[5] Rebecca Solnit, Why We Need New Stories on Climate (The Guardian 2023)

[6] Lucy Neal, Playing for Time: Making Art As If the World Mattered (London: Oberon, 2016)

[7] Photo credit: Breathe:2022, Dryden Goodwin. Image courtesy the artist and Invisible Dust, 2022

[8] John Berger, Hold Everything Dear: Dispatches on Survival and Resistance (London: Verso, 2007)

[9] Main Feature Image: Illustration credit: Silvana P. Duncan for ArtistsForClimate.org at The Greats

For thought partnership and stimulating conversation, thanks to Yazmany Arboleda, Fehinti Balogun, Sarah Browne, Werner Binnenstein-Bachstein, Yana Buhrer-Tavernier, Jo Bradshaw, David Buckland, Holly Donagh, Good Chance Theatre, Henry Hitchings, Hilary Jennings, Sam Lee, Lucy Neal, Kate Keara Pelen, Cassie Robinson, Sophie Schnapp, Alice Sachrajda, Moira Sinclair & Lina Srivastava

For supporting my Clore Fellowship, thanks to Doc Society, Nesta & Synchronicity Foundation